Often called an equal opportunity virus, COVID-19 is “screeching like a heat-seeking missile toward the most vulnerable in society.” That’s how columnist Charles M. Blow described it in the New York Times’ “Social Distancing is a Privilege”.

While it may be true that no one is immune to the novel coronavirus, some have a socioeconomic resistance that protects them from the disease’s most ravaging effects. Others are left exposed and vulnerable.

Exactly who the most vulnerable among us are should not come as a surprise to anyone. Low income workers, disproportionately African American and female. Disabled and elderly people. Immigrants. Already struggling, these are the people least able to withstand a minor setback, let alone the double whammy of a health and economic crisis.

With social distancing the best defense against the virus, many of our hardest working neighbors now risk their lives daily. According to a report by the Economic Policy Institute, nearly 1 in 3 white Americans can work from home but less than 1 in 5 African Americans and 1 in 6 Hispanics have that option. The same report also highlights the disparity in job flexibility based on income: High-wage earners are six times more likely to have the ability to work from home than their low-wage counterparts.

But it’s not just the ability to stay home that determines an individual’s outcome. As the pandemic lumbers its way around the world, the data becomes clear. Those who die from COVID-19 are largely those whose health was already compromised.

In the United States, centuries of unjust policies and practices have led to vastly disparate realities based on race and ethnicity. In “Racism Laid Bare by COVID-19”, the Shriver Center on Poverty Law summarizes not only what led to the current situation but actions to improve it. As the article says, “The virus may not discriminate, but humans do.”

Here in North Carolina, according to the North Carolina Justice Center, African Americans make up 22% of the state’s population but 39% of its confirmed COVID-19 cases and 37% of deaths from the virus. Put another way, in even starker terms, the crude death rate (deaths per 100,000 people) for all North Carolinians is 1.7 but for African Americans it is 3.0.

In a recent webinar, experts from NC Justice Center’s Health Advocacy Project outlined factors behind this disparity. Among them:

- Unemployment and underemployment. The unemployment rate for black Americans is twice that for white Americans. Lack of a job directly impacts a person’s access to health care since most people get their health insurance through their employer. African Americans are also disproportionately more likely to work in low-wage jobs that don’t offer health insurance.

- Racial bias in health care. A popular medical algorithm has a significant racial bias, leading to widespread underestimates of black patients who require specialized care.

- Food insecurity and chronic illness. Lack of investment in neighborhoods of color creates food deserts. Limited access to a healthy diet puts residents at greater risk of developing obesity, heart disease, hypertension, and diabetes, all of which are complicating factors for COVID-19.

- Environmental racism. Exposure to contaminated air and water increases the risk for developing chronic illness. NC Justice Center policy analyst William Munn says that while 25% of all North Carolinians live within a one-mile radius of an EPA-defined polluter, the rate for African Americans is 44%.

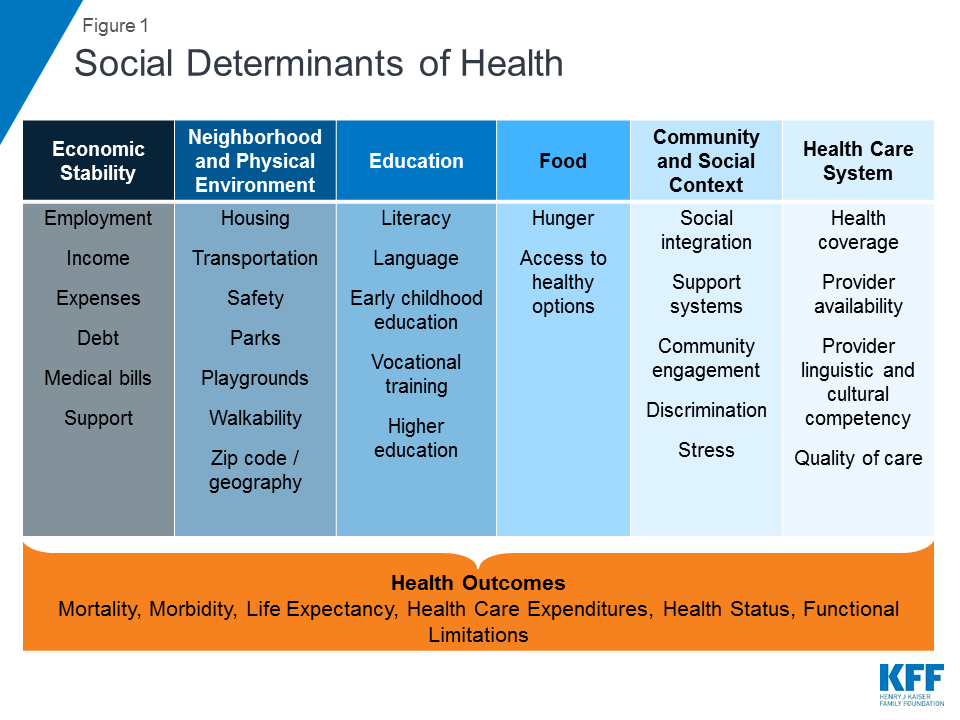

These factors are among the many that comprise the social determinants of health, or how a person’s overall wellbeing is affected by the conditions in which they live, work, and play.

It is no coincidence that marginalized people in our society experience more negative social determinants. Nor is it coincidental that the most vulnerable are suffering the most during this pandemic. Our nation’s complex history of social injustice has effectively placed a bullseye on their backs for the heat-seeking missile that is COVID-19.

Want to know more?

“Covid-19 and Racial/Ethnic Disparities”. JAMA Network. May 11, 2020.

“We Can’t Wait Until Coronavirus Is Over to Address Racial Disparities”. CityLab. April 22, 2020.

“For Charlotte’s black community, coronavirus points to a much larger, complex issue”. Charlotte Agenda. April 20, 2020.