This month, while some of the wealthiest individuals in the world gathered at the annual World Economic Forum in Davos, the charity organization Oxfam released a report detailing how, from the start of the pandemic through the end of 2021, the wealthiest 1% across the globe amassed two-thirds of all new wealth created. This startling concentration of wealth exists in the United States as well. Here, those wealth disparities manifest themselves acutely across racial lines.

This is certainly evident in Charlotte-Mecklenburg, where the effects of the racial wealth gap are visible daily. The fact that more than 8 out of 10 people seeking assistance at Crisis Assistance Ministry are people of color is no coincidence. More than 150 years of policy-induced systemic racism have resulted in the current inequities.

But what if local government could act right now and drastically reduce the racial wealth gap in just a generation?

RACIAL WEALTH GAPS

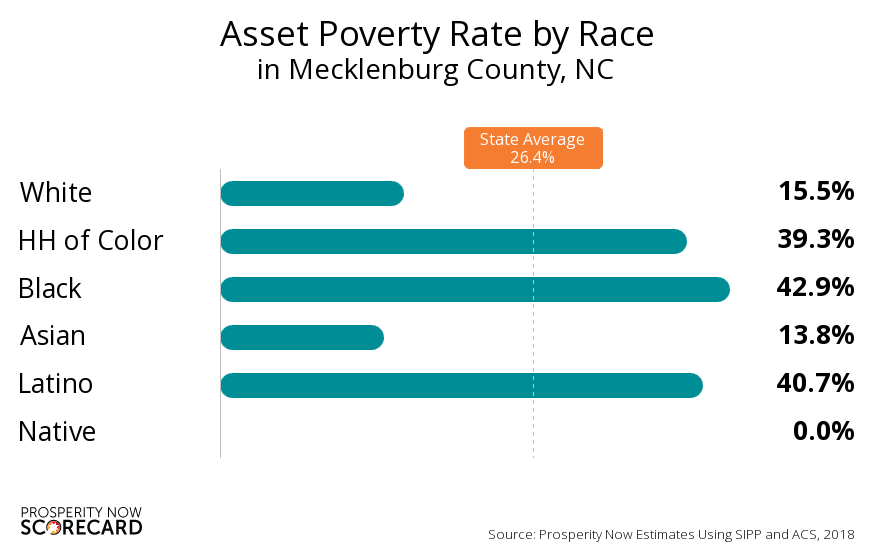

Nationally, the median wealth of white households is ten times that of Black households and eight times that of Hispanic households. Here, in Mecklenburg County, the disparities persist: one in three Black and Hispanic families in Charlotte have a negative net worth, meaning that their total debts exceed the value of their assets. Only one in seven white households in Charlotte experience this. Black and Hispanic households also experience much higher rates of asset poverty, meaning that they lack sufficient wealth to provide basic needs for three months.

By nearly every measure, white families in Mecklenburg County are far better off than Black and Hispanic families. These divides are the product of decades of racial injustice and unfair policy practices in both the private and public spheres.

BABY BONDS

How can we remedy this in the present day? One public policy with potential is commonly referred to as Baby Bonds.

Baby Bonds, in essence, are government-funded trust accounts set up for newborn infants, specifically those born into asset-poor households. The seed money put into the account appreciates in value until the child turns 18, at which point the account becomes accessible to use for a major asset investment like a college education or home ownership. The ultimate goal is to build long-term wealth for those born into economically disadvantaged families. Senator Cory Booker recently proposed the American Opportunity Accounts Act (AOAA), which would provide every American child with $1,000 in an account at birth, plus up to an additional $2,000 per year depending on the income level of the child’s family.

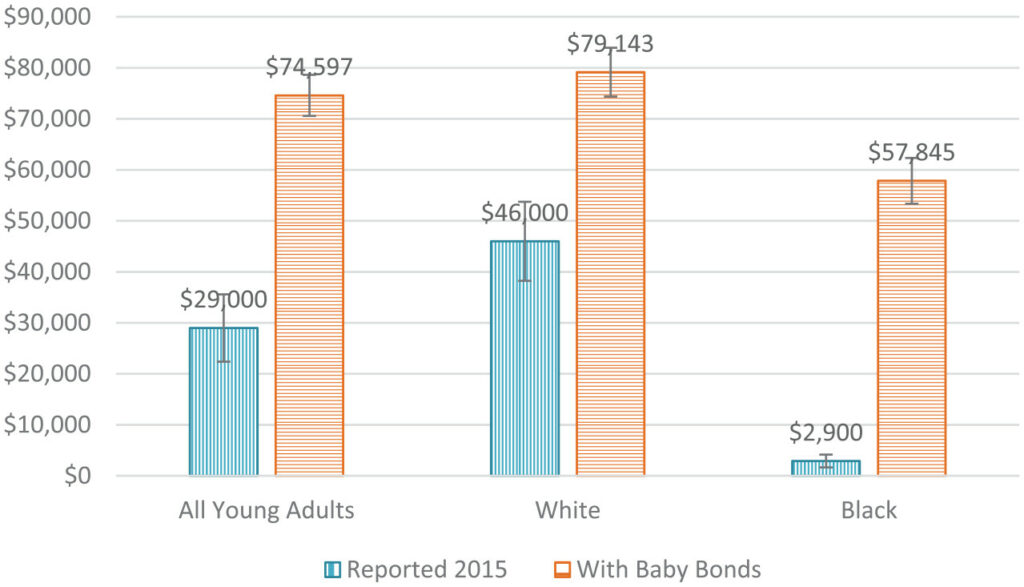

One study from Columbia’s Center on Poverty and Social Policy examined how a hypothetical Baby Bonds program, similar to Booker’s, would have affected wealth inequalities among 18–25-year-olds in 2015. The study found that the program would lower the wealth gap between white and Black households significantly: moving from a difference of more than 10-fold to just 1.4.

While this policy uses income, rather than race and ethnicity, as an eligibility marker, the intricate relationship between race and income potential in the U.S. means it could still do a good job of narrowing the racial wealth gap.

BABY BONDS FOR CHARLOTTEANS?

The impacts of wealth inequalities are quite evident every day at Crisis Assistance where we see people, through no fault of their own, struggling to pay rent, keep the lights on, and afford clothes for their children. In a community that is majority white, the overwhelming majority of people who seek help with basic needs here are Black and Hispanic. But the reality is that the nonprofit sector can only do so much to address the long-term struggles of the economically disenfranchised. Systemic policies have created and sustained the continued wealth gap, and it will require a systemic approach to reverse that impact.

Programs like Baby Bonds apply the power of policy to reduce racial wealth disparities in order to create a more equitable community for us all. While most Baby Bonds programs have been proposed at the federal and state level, Mecklenburg County could consider piloting a bond program for its residents. By creating such a pilot and carefully tracking its outcomes, Mecklenburg County could become a national leader in championing Baby Bonds as well as fighting racial wealth inequality.

Over time, systemic approaches like this could get Crisis Assistance Ministry closer to our ultimate goal: closing our doors because people living in Charlotte-Mecklenburg can meet their basic needs without help from agencies like ours.