Does poverty exist because we want it to?

Matthew Desmond’s new book, “Poverty, By America”, asks this and other provocative questions about persistent poverty in our land of plenty.

Conversations about poverty in the United States are generally centered around two prevailing narratives: first, the patently false notion that the impoverished only have themselves to blame for their situations, a product of poor choices that have led them to their current predicament; and second, the idea that systemic issues, such as wage stagnation, lack of affordable housing, and a lackluster social safety net, are the root causes of the comparatively high rates of poverty in the U.S.

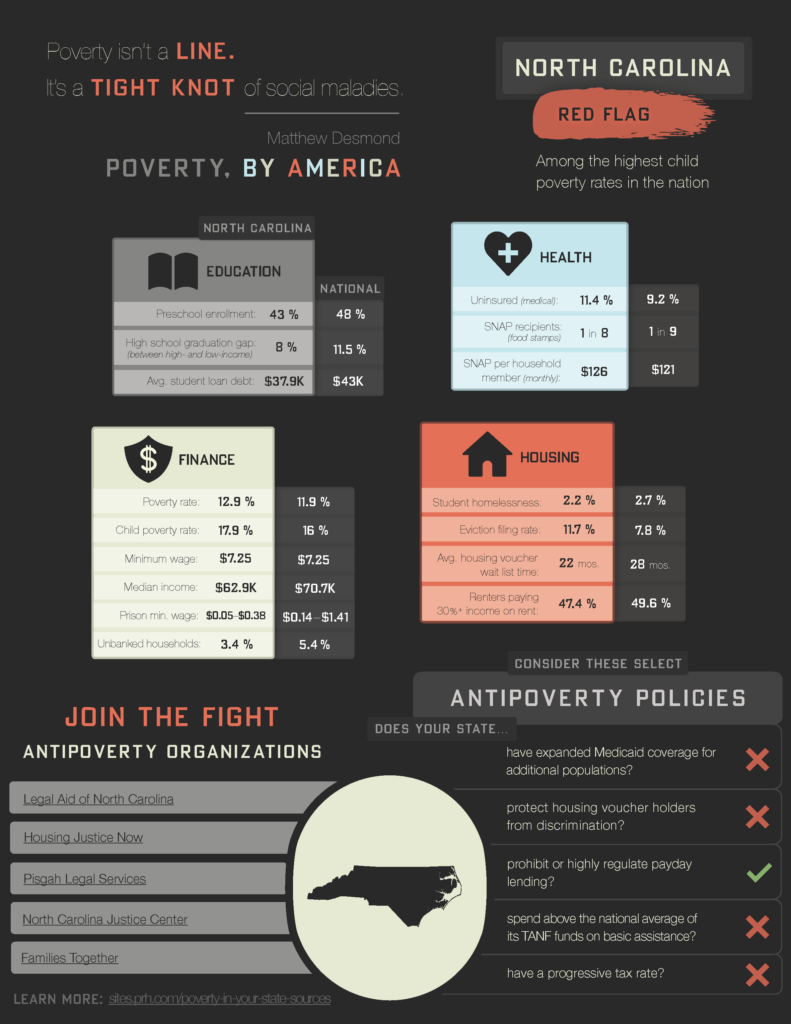

In “Poverty, By America,” author Matthew Desmond, professor of sociology at Princeton University, lends a great deal of credence to the systemic narrative, exploring how factors like the rising costs of rent, a broken welfare system, and the diminished power of unions have all contributed to the outsize rates of poverty we see in the U.S. However, Desmond also offers a new explanation for the current state of affairs: widespread poverty exists because we want it to.

And by “we”, Desmond does not mean the multimillionaires and billionaires of the top 1% and .1%, toward whom many antipoverty advocates focus their ire. Instead, the “we” is us: middle and upper-middle-class Americans, the comfortable, those with stable housing. Desmond does focus on individual choices that contribute to higher poverty rates. But he isn’t referring to people living at the poverty line. Instead, he points directly to the choices of Americans living in relative comfort and prosperity.

The Rudest Explanation

Desmond admits this is the “rudest explanation,” but he makes his case rather convincingly. Looking at the American welfare state, he points out that while the federal government is rather generous in how much it spends on aid programs, it is difficult for those who most need that aid to access it. He uses data to support this claim, including how only a quarter of families who qualify for Temporary Assistance for Needy Families apply for the assistance. Desmond estimates that nearly $142 billion in aid for low-income Americans goes unused each year. As he puts it, “the problem is not welfare dependency but welfare avoidance.”

While welfare avoidance plagues low-income Americans, “the rest of us, we members of the protected classes, have grown increasingly dependent on our welfare programs,” Desmond states. In fact, looking at how the federal government distributes social insurance, means-tested programs, tax benefits, and financial aid, Desmond finds that the average household in the bottom 20 percent of incomes receives $25,733 in government benefits a year, while the average household in the top 20 percent of incomes receives $35,363 in benefits per year. Public benefit spending in the U.S. is the second highest in the world as a share of its GDP; however, in terms of benefits that directly target low-income citizens, we spend much less than other comparatively wealthy nations.

Desmond points out this data to show that perhaps the status quo has persisted for so long because of how beneficial it is to those who are well-off. This includes those who are often the loudest champions of antipoverty measures. In his discussion of housing and zoning policies, Desmond states that “Democrats are more likely than Republicans to champion public housing in the abstract, but among homeowners, they are no more likely to welcome new housing developments in their own backyards.” He adds, “Perhaps we are not so polarized after all. Maybe above a certain income level, we are all segregationists.”

Desmond’s intent is not to shame those who are comfortably well-off. Rather, he calls us to take inventory of our lives, to see how we are potentially contributing to the problem of poverty, and to make changes. Desmond calls himself a “poverty abolitionist,” and invites us to join him. He admits it isn’t easy: “Poverty abolitionists do the difficult thing. They donate to worthy organizations, yes, but they must do more. If charity were enough, this book would be irrelevant. Giving money away is a beautiful act, yet poverty persists. Rather than throwing money over the wall, let’s tear the wall down.”

Learn More

Download A Discussion Guide for “Poverty by America