On World Mental Health Day, we find ourselves examining the connection between poverty and mental illness.

Of course, it is not fair to say that all low-wage earners are mentally ill. Nor is it accurate to say that all people with mental illness live in poverty. Still, evidence shows that the two are often related.

Defining the connection is a chicken-and-egg scenario: does mental illness create an inability to overcome a state of poverty, or does poverty increase or perpetuate the occurrence of mental illness?

Here at Crisis Assistance Ministry, we see the implications of the cycle of mental health and poverty daily. While our neighbors most often come to us for basic material needs (rent, utilities, clothing, shoes, furniture, appliances), we know there is much more going on behind the scenes.

Is it the neighborhood?

People who live in neighborhoods with high rates of poverty “exhibit worse mental health outcomes compared to people in low-poverty ones,” according to the National Association of Mental Illness (NAMI). This cuts across ages, with both adults and children experiencing significant mental health effects from living in poverty. According to NAMI, Hispanic people are three times more likely to dwell in high-poverty areas than white people who are poor, and African American communities are five times more likely. As a result, these marginalized populations are also more likely to experience mental health difficulties.

Certainly, dwelling in the stressful state of poverty can worsen mental illness or ignite it. The instability that often accompanies mental illness can also lead to poverty on its own. The cycle continues and grows as more people find themselves reeling from the physical, financial, and emotional impacts of the pandemic, too.

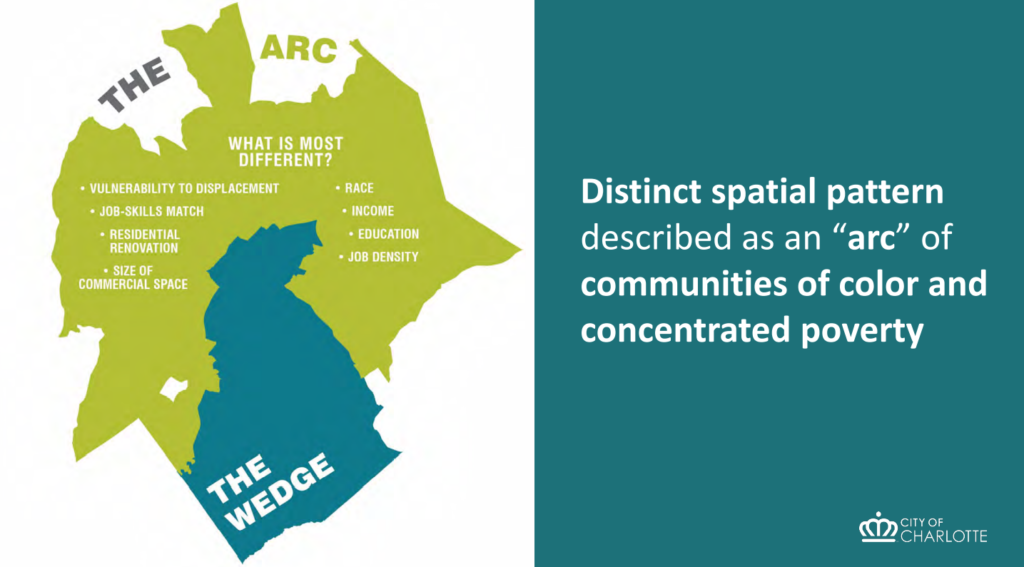

In Mecklenburg County, breaking that cycle becomes difficult if one is born outside “the wedge,” stretching through the center of Charlotte into south Charlotte. It’s surrounded by a “crescent” or “arc” of lower-income, high-poverty zip codes. Being born into a lower-income zip which lacks accessible, affordable, and/or quality resources often means your income will remain lower and your economic mobility limited. This can have negative impacts on mental health.

retrieved from “Charlotte’s Arc and Wedge,” https://www.cltpr.com/articles/arc-wedge

By the numbers

While the impacts of mental illness are most often evident anecdotally, there are plenty of numbers to consider:

- Locally, the Leading on Opportunity report shows that more than one in five children in Mecklenburg County live in families who earn less than the federal poverty level ($27,750 for a family of four). The median income for African American and Latino families in the county is about half that of Asian and white households.

- The 2019 Mecklenburg County Community Health Assessment found more than 157,000 adults in the county reported being diagnosed with depression. A third of Mecklenburg County students reported “being so sad almost every day for two weeks or more in a row that they stopped doing some activity.” The next assessment will be published in 2022.

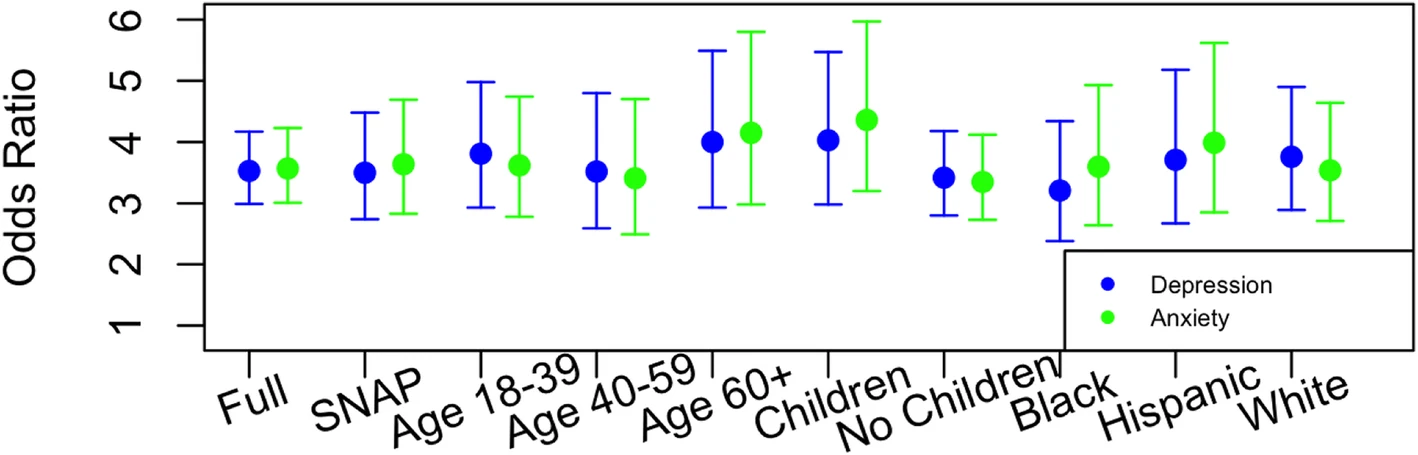

- Food insecurity runs parallel to a higher risk of anxiety and depression, according to the BMC portfolio of peer-reviewed journals. Pandemic-related job losses pushed those numbers higher, the BMC shows.

The association between food insecurity and mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic

Taken together, the intersection of economic struggle and mental health is clear, even if we can’t isolate which one leads to the other.

Struggle = Stress

Participants in our poverty simulations often comment on the level of stress they feel as they walk for a brief time in the shoes of their low-income neighbors. They say the mental anguish sticks with them once the simulation ends and they return to their regular lives. It’s a brief glimpse into the daily struggle many Charlotteans continue to experience—even in the shadows of our city’s gleaming skyscrapers.

Resources are available

If you know someone who is struggling with their mental health, contact Mental Health America of Central Carolinas, (704) 365-3454. Their 10 Tools to Live Your Life Well also includes useful information for managing mental health and self-care.